Does Womens Empowerment Encourage Good Global Citizenship

These days, when the going gets tough, women “increase the peace.” From U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to Liberia’s President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the international community has...

These days, when the going gets tough, women “increase the peace.” From U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton to Liberia’s President Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, the international community has learned that women’s leadership can contribute a different voice to fostering peace, alleviating poverty, and fighting for the rights of the oppressed.

Countries like Canada and Sweden that are known for promoting peacekeeping; drafting and staffing international law; and providing humanitarian aid are also deeply democratic and gender-friendly, with significant participation by women in diplomacy, decision-making, and civil society.

Perhaps, then, there is a link between women’s empowerment and good global citizenship.

But the relationship between gender and foreign policy needs to be assessed more carefully. Extraordinary leaders may be exceptions or distractions from more important drivers of foreign policy – like a country’s own development, culture, or human rights record. Individual female leaders and diplomats like Margaret Thatcher or Condoleeza Rice have been just as aggressive as their male counterparts and not necessarily sensitive to humanitarian issues or traditional “women’s concerns.” It may be important to give women greater access to decision-making as a matter of fairness, but we cannot assume it will magically transform global problems – especially as any new group entering power tends to conform to established norms.

And if empowering women does encourage good global citizenship, we need to know how and why: is it leadership, grassroots pressure, improved consciousness, or something else that has an effect on how countries behave?

Deep Democracy

To better understand these dynamics, I worked with my economist colleague Aashish Mehta to do a controlled statistical study of the relationship between gender empowerment and a wide range of indicators of humanitarian foreign policy, recently published in the Journal of Peace Research. We controlled for the influence of other factors that previous studies have shown influence foreign policy, from levels of development to democratic governance and membership in the Western bloc. We believed that the widespread empowerment of women in a society, beyond the work of particular leaders, would be linked to better performance by that country in promoting global human rights.

Social science and international relations suggest several logical reasons that empowering women should make a difference.

First of all, we know that democracies are more peaceful and better global citizens. One reason for the “democratic peace” effect is greater citizen engagement in foreign policy, so “deep” democracies that foster greater participation by half of their population should be even more responsive to citizen concerns and global linkage. Case studies of women’s participation in human rights policies in countries like Canada suggest the deep democracy effect does operate in some places.

Next, women across the globe are more affected on average as victims of war, poverty, and human rights abuse. Worldwide, women tend to care – and organize across borders – more on these issues. In the developed countries that drive most aid, treaties, and international programs, there is a “gender gap” in women’s voting behavior and civic participation towards policies and movements for peace, human rights, and poverty alleviation. Existing research also confirms that countries with stronger women’s movements have stronger international policies to combat violence against women.

Finally, surveys show that women’s empowerment generates (and reflects) cultural change in the attitudes of all members of a society towards more collaboration, tolerance, and global concern. Modernization and participation in global institutions also raise consciousness about the linkages between gender equity and national concerns like economic development, public health, population, and environmental sustainability, in a reinforcing circle. This public opinion effect is strongest for the most educated sectors, so it should certainly be relevant for highly trained diplomats and political elite decision-makers. This suggests greater gender equity across society socializes more citizens to prefer a more peaceful and balanced world and encourages global consciousness in notions of national interest.

Gender Equity Leads to More Humanitarian Policies

Overall, our study confirmed that greater gender equity leads to more humanitarian foreign policy. We found the strongest relationship between the broadest measure of women’s empowerment and a country’s participation in global initiatives against violence, child abuse, anti-discrimination measures, and higher-quality foreign aid. Countries with strong women are generally better advocates against all forms of human rights abuse, including issues like the death penalty that mainly affect men (the vast majority of people executed are male).

But there are limits to the extra influence of women on more contested issues with more players from the foreign policy establishment, notably adherence to the International Criminal Court, trade concessions that go beyond aid, and the adoption of sanctions against pariah nations. All of these issues are also improved by a country’s level of democracy, and in several cases, the influence of women’s empowerment interacted with levels of democracy, suggesting the deep democracy effect is more powerful where all citizens have greater influence on foreign policy.

We also tested several dimensions of women’s empowerment as a driver of foreign policy to try to identify some of the linkages and pathways of influence. Breaking down women’s empowerment into dimensions of political representation; economic and social conditions; and gender-specific rights to try to see what “does the work” of affecting foreign policy, we found women’s political participation was most tied to improving aid and least important for global anti-discrimination measures.

We also found an association between living in a society with better women’s rights and support for humanitarian outcomes that crossed gender lines, suggesting a broader socialization to tolerance and human rights promotion by decision-makers and diplomats in these societies.

Thus, we found some evidence to support each pathway to good global citizenship: women’s leadership, grassroots pressure, and consciousness-raising all seem to matter in different ways.

This study reinforces the idea that gender equity supports good global governance. It’s also a reminder that promoting social change is a much broader process than promoting individual leaders, and democracy means more than electing different leaders – it means including different citizens. Promoting women’s rights is not just the right thing to do; it is in our national interest. Our best allies on global humanitarian issues will be societies that take equality seriously at home.

Torture Doesn't Work: It erodes national security and democracy.

SAN DIEGO - A morally bankrupt foreign policy. A degeneration of democratic checks and balances. Those are just a few of the disturbing facets of the state of the US government revealed...

SAN DIEGO - A morally bankrupt foreign policy. A degeneration of democratic checks and balances. Those are just a few of the disturbing facets of the state of the US government revealed by the debates over the confirmation of Attorney General Michael Mukasey and his views on whether waterboarding constitutes torture.

But the deepest irony of the Bush administration's ambivalent stance on such medieval tactics – practiced in the name of defending national security – is that torture is not only wrong, it's also a stupid strategy that undermines the defense of democratic societies against terror.

US leaders must correct their profoundly mistaken analysis and ignorance of the lessons of history about torture.

Torture is an ineffective counterinsurgency strategy. One defense of torture is the "ticking bomb" scenario – the idea that an imminent, massive threat to civilians might be stopped by a single detainee who possesses crucial information and will yield actionable intelligence under physical coercion. But this is mostly a law-school legend, not a frequent occurrence in a complex conflict with multiple levels of planning and diffuse local support.

Despite fearful anecdotal claims, the effectiveness of torture in generating intelligence is questionable at best. But we do know that torture produces many false confessions and new enemies, and distracts from more effective, legitimate techniques of interrogation and intelligence-gathering. We also know that democracies that have turned to torture in counterinsurgency – for example, the French in Algeria – have lost, while the British found a solution in Northern Ireland after they gave up abusive tactics.

Torture escalates conflict. The use of torture by targeted societies is strongly associated with an increase in the severity of terror used against them. In interviews with imprisoned terror leaders from the Palestinian territories to India, they state that they adopted and were supported in bloodier tactics when democratic enemies resorted to torture and attacks on civilians.

The "torture-terror nexus" can be seen in Israel. The first intifada was militant but largely peaceful, while the second intifada was characterized by suicide bombings. The tough Israeli response to the first, which an Israeli inquiry showed involved the mistreatment of about 85 percent of Palestinian prisoners, appears to have temporarily suppressed one uprising while planting the seeds of greater violence in the next.

Torture blocks international cooperation against terror among valuable democratic allies. America's adoption of illicit tactics has undermined the legal cooperation that is our best weapon against transnational terror. In Germany, an important prosecution of a terror suspect was handicapped because US evidence gathered in Guantánamo was legally inadmissible.

A Spanish prosecutor has stated that he is unable to order extraditions to the US, as a country that violates Spanish legal guarantees.

In Afghanistan, Canadian and Dutch forces holding critical contested areas are not permitted to release Afghan captives to US facilities where they might be mistreated, deported to Guantánamo, or "rendered" to abusive countries. This policy came into effect after pressure from the Dutch parliament and Canadian courts, on behalf of outraged democratic publics.

Torture drives out legitimate policing. Preventing terrorism is a question of good police work, built on strong ties with the communities that host insurgents, sophisticated knowledge of criminal networks, and swift cooperation among agencies and allies. But current US tactics alienate global publics and local communities, while the secrecy torture requires fosters bureaucratic bungling. Frustrated FBI and military intelligence professionals have resigned, citing sloppy and illegal coercive interrogations by an unaccountable collection of reservists, military police, CIA agents, and private contractors.

Torture undermines the rule of law and corrupts democratic institutions. Democracy is the system the US is fighting to defend. It is also the best defense of US national security – like the rule-of-law strategy that has enabled the United Kingdom to forestall some attacks.

Similarly, America's credibility in promoting democratic reform among unstable front-line allies such as Pakistan depends on honoring its international commitments such as the Convention Against Torture. US commanders believe that adherence to the Geneva Conventions helps ensure the safety of the troops. Democracies that use torture become less democratic, as illicit interrogations are hidden from public view, outsourced to unaccountable special services, diverted to parallel legal systems such as special tribunals, and removed from congressional checks on executive power.

The authorization of, or acquiescence to torture, by US senators is a betrayal of the Constitution they have sworn to defend. It defies the wishes of the majority of Americans of conscience, and it compromises US national security. We must demand that our elected leaders not pander to the politics of fear, but rather meet their responsibility to provide an intelligent, sustainable, and humane national defense.

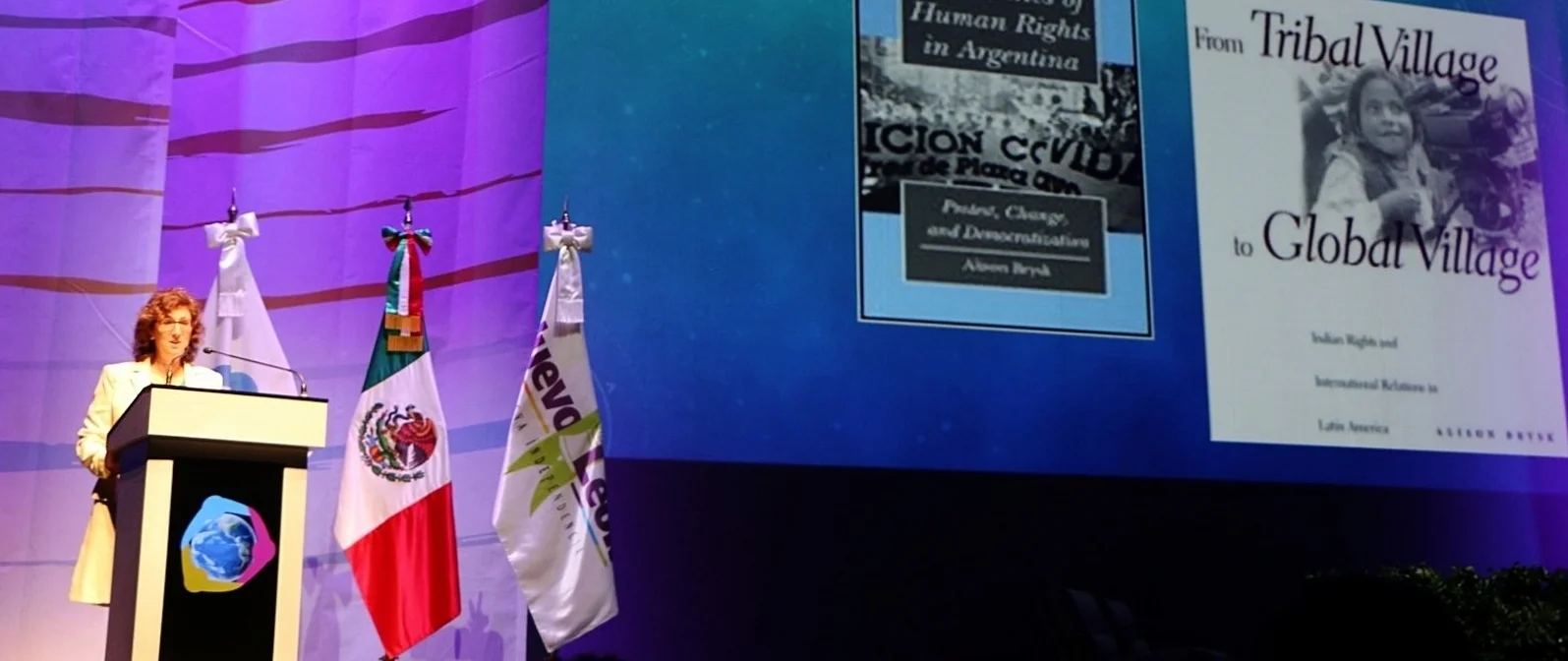

Alison Brysk is a professor of political science at the University of California, Irvine, and co-editor of "National Insecurity and Human Rights."